So the AI came for me. Not in the preposterous Skynet style science fiction way that apparently serious people waste vast amounts of other apparently serious people’s time warning them about, but in he mundane everyday way that already has an impact on the lives of millions of people around the world.

I got an email from my electricity supplier telling me their projections showed my energy bills should be massive, so they had quadrupled my payments. This despite the fact that I am currently using less electricity than I pay for and my account is over £500 in credit. I wrote to them and told them all this and to their credit they changed my payments back to what they were. However, the only reason this happened in the first place was because they let the AI decide how much I should pay without a human doing a sense check.

I am an outlier. At the start of last year I had a heat pump installed, which on its own shouldn’t make me an outlier, except that before the heat pump I had an electric combi boiler heating my house. So unlike most people, whose electricity use will go up when they switch from a gas boiler to a heat pump, my usage more than halved. So I really am an exception, I am a scenario that is never going to fit the data model and no data scientist would try and make me fit the data model. That would be what they call ‘overfitting’, which would distort the data model and stop it working properly for all the other more ‘normal’ customers.

This is what some AI evangelists either don’t understand or don’t say: any data model is designed to be very accurate for the most common results and the largest number of scenarios, but not all of them, and it can’t be trained to account for every scenario, because that requires genuine intelligence and genuine understanding. Nothing built in the ‘AI’ space thus far has the ability to make a value judgement that isn’t ultimately quantitative, so must always tend towards some version of a mathematical mean. And any kind of average, even a very complex one, will have exceptions.

I had a call with an AI startup recently, where in the middle of presenting quite an impressive product, they were keen to point out that they had no intention of removing humans from the loop, but that the system would take “the grunt work” out of what I know to be a very human intensive process (for something that involves computers). I found it refreshing that a company clearly (and justifiably) very confident in the capability of their AI was also very cognisant of the fact that certain aspects of precision require a human being.

In financial services, we aren’t really allowed to get the wrong answer, we are (rightly) expected to account for every penny of our customers’ money. Consequently systems have built up that can give accurate outcomes and require very specific inputs. Some more complex or nuanced transactions are passed off to people, not because they are too complex to automate, but because there is not a clearly defined outcome or range of outcomes. In many cases it is not clear that all of the possible outcomes of the process have yet been achieved, realised or thought of. If anyone tells you that these processes could be fully automated if you just used AI, they are lying. What we call AI – whether that is the LLMs that are currently called AI or the other various forms of machine learning, deep learning, etc that have previously bourne the moniker AI – relies on the knowledge of previous outcomes, whether that is text, images, code or disability benefit decisions. It has to have happened before, or be a possible outcome directly, statistically relatable to what has happened before. What we call AI is merely crowdsourcing statistical programming algorithms. At a granular level the outcome must be defined the same as for any other ‘dumb’ programme, but the fact that there are so many possible outcomes from the many millions or billions of calculations that go into making an AI algorithm means that they give the appearance of nuance.

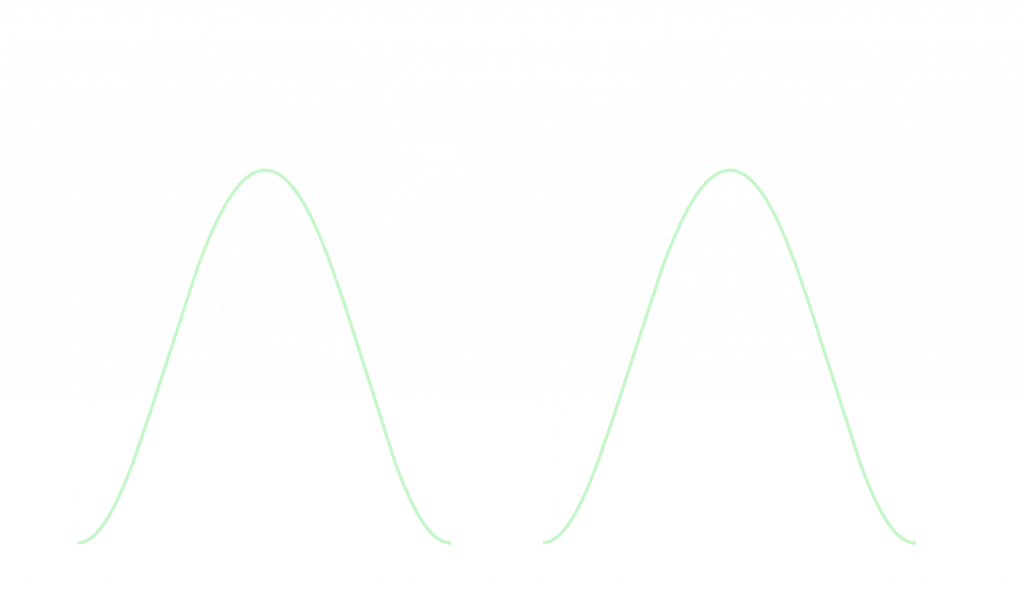

When CDs came out, many audio purists complained that they sounded flat and lifeless, and there was an element of truth to this. Whilst a sound wave is a smooth curve, the 16 bit sampling of CDs could only pick up certain points on that curve, meaning that there is ‘less’ of a sound on a CD than on a vinyl record for example. It is an approximation of the sound that has been recorded, and with high quality audio equipment, you can ‘hear’ the gaps (I don’t mean literally, but you can tell the difference between a record and a CD). As digital technology and data storage capacity have improved, we’ve moved to ‘lossless’ digital audio, which doesn’t mean that we have digitally recreated the full sound wave, but rather that the ‘gaps’ have got so small that the human ear cannot tell the difference. It is still a simulation of the real sound wave, but now it is so close that it is ‘as good as’ real.

In terms of simulating the particular portion of reality that they are trained on, AI systems are currently at best at CD quality, and in most cases that would be a CD with a couple of annoying scratches on it. The challenge with getting them to an equivalent of lossless is their complexity. With a sound wave, you can see what the analogue waveform looks like and you can match your digital replica to it exactly to make sure it is right. With an AI algorithm, the number of possible outcomes mean that no human or team of humans could ever fully validate it. It is like looking at the night sky and trying to work out which stars are in the wrong place. This is why even the most expensive AI tools, trained on most of the data available on the internet and beyond still ‘hallucinate’ (what used to be called getting the wrong answer) and indeed why they always will. As I mentioned before, the aim of data science is not to get the exact right answer every time, but the most probably correct answer. Even this is impossible to achieve completely in a very large model because you can’t even test the most probable outcome of every scenario with anything except another large AI data model that you can’t prove is correct for the exact same reasons.

So if we are stuck in a world where everything produced by AI has the potential to be wrong (even if only in exceptional circumstances), what can we do? First, make sure that we understand where applications of AI will not actually lead to ‘wrong’ answers. High finance has been using machine learning, deep learning and similar forms of ‘AI’ for years, because the predictive outcomes associated with such models can give usable ranges of risk ratings or investment approaches. Here there is not necessarily a single point answer, but a range of answers or at least a tolerance for deviation.

Another option is to use AI to get you close to the answer and then pass it over to a human to finish, previously identified as ‘letting the AI do the grunt work’. This allows for complex or specific outcomes and avoids the kind of boo-boo that my energy provider let the AI get away with. You can even use AI itself to identify when the result potentially needs checking. As something fundamentally based on statistics an AI algorithm should be able to identify when its result is outside of the standard deviation for results and report a potential exception. At the very least you should not begin with an assumption that the machine is right, and in all cases it pays to maintain a strong control of your training data. If you want your AI to give accurate specialised results, don’t train it with all the data on the World Wide Web. In short don’t try to use ChatGPT to write a legal contract.

Finally, the deeply unfashionable answer: consider whether you should be using AI at all. Even if you can get the right answer from AI, building and training an AI is energy, money and resource intensive. If ‘traditional’ programming can yield the same results, why would you consider the additinal effort of AI? It would be wasteful and inefficient. If you are considering a new implementation of anything where an AI solution has been proposed, you should always be asking yourself this question: can this be done quicker, more efficiently and more effectively with regular programming?

Why am I writing all this? Well, when people ask me what a Solutions Director does, the answer is consider these sorts of things. Whilst developers and product owners (rightly) get excited about what a product can do, my team and I occupy our time working out what it should do, how it should do it and whether it should do it at all (or whether we should be using a different product). So I’m writing about it because it’s what I think about, but also because there should be more people thinking about it. AI is going to be applied to many critical applications over the coming years and we need to be aware that it can have serious consequences. If I had been a vulnerable person or a pensioner who had been told the computer had calculated that my bill needed to quadruple, I may have accepted that and tried to find a way to pay it. If it had been an AI assessment of disability benefit that didn’t understand my condition and cut me off, that would be life changing in all the wrong ways. Over the next few years we’re going to see stories of AI ‘hallucinating’ things a bit more serious than 7 fingers. It’s up to those of us responsible for implementing these systems to make sure they are implemented correctly and in the correct context, minimising risk of harm or error. In terms of how we decide and plan how software is deployed, nothing has really changed with AI, much as some people want you to think it has. At the end of the day it’s still just software.

Leave a Reply